This Week’s Theme: Unenforceable Ideals

This week, we explore three unenforceable ideals—situations where two conflicting truths can’t coexist.

First, we draw parallels between Prohibition and illegal immigration, highlighting the government’s struggle to control the demand for goods and services.

Second, we examine the logical inconsistency of supporting stricter climate change regulations while opposing overturning Chevron deference.

Last, we address the contradiction of prioritizing military effectiveness while excluding women from combat roles.

Let’s begin with the story of Mabel Walker Willebrandt and her fight to enforce Prohibition.

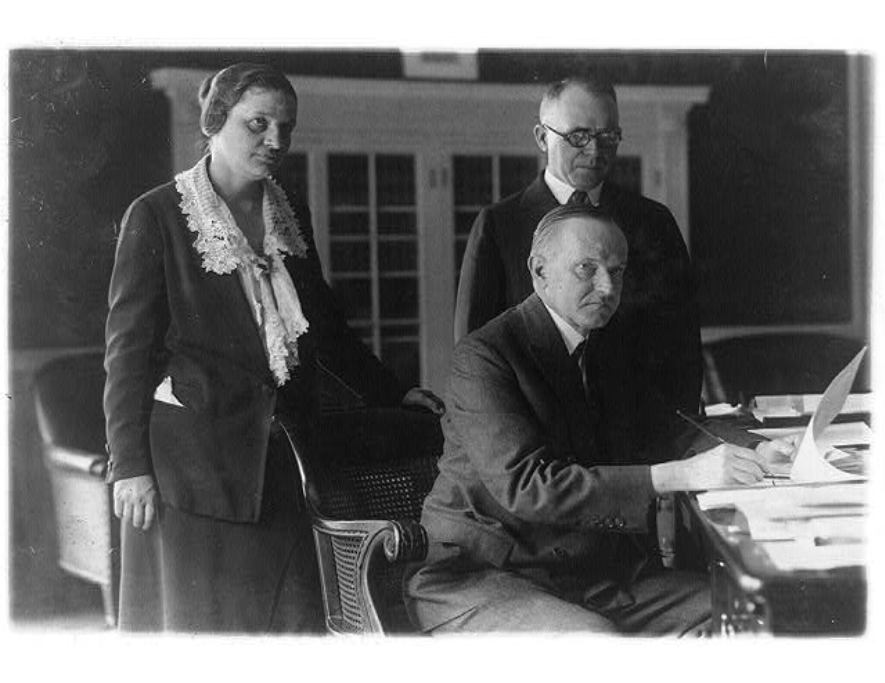

The First Lady of Law

In 1921, President Warren Harding appointed Mabel Walker Willebrandt to the office of Assistant Attorney General of the United States. The appointment made Mabel the highest-ranking woman in the US government in the 1920s. Among her other duties as Assistant Attorney General, Ms. Willebrandt was charged with enforcing the Volstead Act, or National Prohibition Act. Congress passed the Volstead Act to enforce the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, which attempted to ban the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors.”

Ms. Willebrandt recognized that enforcing Prohibition through raids on speakeasies and small-time bootleggers was ineffective. She described this as “like trying to dry up the Atlantic Ocean with a blotter.” Instead, she enforced the Volstead Act with a two-pronged effort: addressing tax evasion and targeting major criminal enterprises.

Her first effort, addressing tax evasion, was successful. During her service, Willebrandt argued more than 40 cases before the Supreme Court. One of the most decisive was United States vs. Sullivan (1927). In that case, Willebrandt argued, and the high court agreed, that illegal income was taxable. Because illegal income was taxable, failing to declare income from illegal operations was tax evasion and a felony offense.

Since illegal alcohol sales generated untaxed income, US vs. Sullivan gave the federal government the authority to investigate and prosecute these operations under tax laws. This effort weakened the finances of organized crime. Willebrandt used the precedent set by US vs. Sullivan to prosecute powerful gangsters such as Al Capone for federal tax crimes.

Her second effort, targeting major criminal enterprises, was less effective. It required coordination across multiple federal and state agencies, which often lacked resources and cooperation. Criminal networks adapted faster than enforcement efforts, developing new smuggling routes and distribution systems that outpaced government responses.

Willebrandt’s second effort failed because Prohibition lacked broad public support. In other words, Americans wanted to drink, and no effort by the federal government was going to reduce the demand for alcohol. Although the government found some success in raiding production facilities and intercepting smuggling operations, these initiatives amounted to a game of Whac-A-Mole. As soon as one network was dismantled, another rose in its place.

The failure of Prohibition enforcement is a story about human behavior and governance: government attempts to restrict supply without addressing demand fail. Banning alcohol supply didn’t stop demand; it fueled a thriving black market. Speakeasies became social hubs, and even law-abiding citizens began to view Prohibition as government overreach, fueling resentment toward enforcement.

If we can’t turn off the demand for an item, no government effort to restrict supply will stop it.

This concept also applies to undocumented immigration. Addressing illegal immigration is a complex challenge that, like Prohibition, requires coordination among federal, state, and local agencies, each with competing interests and limited resources.

The most significant hurdle is the strong demand for undocumented labor. Many immigrants risk their lives to come to the United States because they believe they can find employment opportunities. Some employers hire undocumented workers because they may accept lower wages and work under conditions that others refuse.

If businesses face real consequences for hiring undocumented workers, the incentive to cross the border illegally would diminish. By enforcing laws that require employers to verify legal residency, we address the demand side of the issue.

Attempting to control illegal immigration solely through border enforcement is like playing a game of Whac-A-Mole—without reducing the demand for undocumented labor, these efforts are unlikely to succeed.

We can’t advocate for removing undocumented immigrants while opposing requirements for employers to hire legal residents. Turning off the demand for undocumented labor is a critical first step toward resolving illegal immigration.

Alternatively, we have another option. We don't have to shut off the immigrant pipeline for businesses. By expanding immigrant work programs and accepting more legal immigrants, we can align immigration policies with the economy's labor needs. This approach addresses the demand for workers legally, supporting businesses while upholding the rule of law.

The second unenforceable ideal from this week is the inherent logic fallacy of supporting stricter rules for climate change while opposing overturning Chevron deference.

The Second Unenforceable Ideal: Climate Change and Overturning Chevron Deference

Let's consider the inherent contradiction of supporting stricter climate change regulations while opposing the overturning of Chevron deference.

On November 25, 2024, the New York Times “The Morning” email discussed climate change regulations. Advocates for robust environmental regulations push for limits on pollution from automobiles, power plants, and factories. They support expanding access to renewable energy and reducing reliance on fossil fuels. Opponents are concerned about the economic impact of stringent regulations and favor a more measured approach.

That morning’s email posited the new administration plans to repeal pollution limits on automobiles, power plants, and factories and expand access to federal oil and gas drilling land. Many of these regulations were established through federal agency interpretations of ambiguous statutes—a process enabled by Chevron deference.

This discussion isn’t about the merits of specific climate policies. It’s about governance and how laws are made and enforced.

The decisive juncture is not the potential repeal of these regulations. It’s Chevron deference, which the Supreme Court overturned on June 28 of this year. Established by the Supreme Court in the 1984 case Chevron USA vs. Natural Resources Defense Council, the Chevron doctrine held that courts should defer to a federal agency’s reasonable interpretation of an ambiguous statute that the agency administers.

Under Chevron deference, federal agencies had been empowered to interpret vague or broadly written laws, effectively creating law without direct congressional approval. The judiciary then deferred to these interpretations, limiting its role in checking executive overreach, alignment with congressional intent, or constitutional principles. While this allowed for faster policy implementation, especially in complex areas like environmental regulation, it also concentrated legislative power within executive branch agencies. The practice bypassed the legislative process, blurred the separation of powers, and weakened constitutional governance.

This violated the Constitution. Article I, Section 1 states that all legislative powers reside in Congress. Allowing agencies to legislate through regulation concentrated power in the executive branch. Chevron deference undermined the legislature’s responsibility to fulfill its constitutional duty.

Article III outlines the judiciary as the independent interpreter of the law. Further, in the precedent case Marbury vs. Madison (1803), Chief Justice John Marshall established, “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” Chevron deference stripped the judiciary of its authority to conduct checks and balances.

America owes allegiance to no king, and this principle of divided power is fundamental to American liberty.

Overturning Chevron requires Congress to pass meaningful bipartisan legislation rather than the watered-down ambiguity that federal agencies use to create de facto laws.

Again, this isn’t about climate change regulations; this concept applies to all regulations. When the executive branch changes, the country shouldn’t drastically change directions. Federal agencies need to adhere to Congressional legislation, and overturning Chevron deference helps restore the nation to constitutional footing.

We can’t oppose overturning Chevron deference while resisting a new administration’s ability to change agency rules. When agencies have broad interpretive power, regulations change dramatically with each administration, leading to policy instability. Upholding the constitutional separation of powers ensures that laws remain consistent unless altered by Congress.

To achieve lasting and effective climate policies, we should support legislative action that clearly defines regulations and goals. This approach respects the Constitution and provides stability, regardless of changes in the executive branch.

Our final unenforceable ideal this week is the inherent contradiction in claiming to prioritize the military’s ability to achieve decisive effects while excluding women from combat roles.

Viper 72 is ‘Winchester’

On April 13 of this year, Iran launched a series of missile and suicide drone attacks against Israel. Iran’s attack was an operation designed to overwhelm Israel’s air defenses. The US condemned the attack and assisted Israel in shooting down the vast majority of missiles and drones.

The nation awarded Major Benjamin Coffey and Captain Lacie Hester the Silver Star for their actions as ‘Airborne Mission Commanders’ that evening. As the command team aboard their F-15E Strike Eagle, they led their squadron that evening to shoot down 70 Iranian drones and three ballistic missiles headed towards Israel. The award is especially significant for Captain Hester, who became the Air Force’s first woman and the tenth woman in the Department of Defense to win the Silver Star.

The Strike Eagle is a complex weapons platform that delivers precision firepower while operating in demanding combat environments. Its advanced systems integrate radar, electronic warfare capabilities, and air-to-ground or air-to-air munitions. The Strike Eagle is a cornerstone of modern air superiority and interdiction missions.

Captain Hester is a weapons system officer (WSO) on the platform. Aboard the Strike Eagle, the pilot and WSO have some interchangeable capabilities. The pilot’s primary duty is to fly the jet. The WSO primarily manages the complexity of coordinating with other assets, identifying targets, and selecting suitable munitions. A WSO’s role is critical to the platform’s mission success. They operate the advanced radar, sensor, and targeting systems that guide the aircraft’s weaponry, enabling precision engagement of air-to-air and air-to-ground threats. They are the tactical brains of the operation.

That’s just Captain Hester’s role on her own platform.

As Airborne Mission Commanders, Major Coffey and Captain Hester take on responsibilities beyond their platform. They are the squadron mission lead, coordinating an entire air mission in real-time. They oversee multiple aircraft, synchronize their actions, and ensure every asset is in the right place at the right time to achieve mission objectives.

Major Clayton Wicks was monitoring a command and signal frequency that evening. Of the event, he said, “A message comes across that just says … Viper 72 is ‘Winchester,’ which means they are out of missiles. They have no bullets left. … That was the first time I was like, ‘Oh my gosh. Command and control can’t keep up with the amount of missiles that are being shot and things that are happening. And that’s the only message they got across.”

In the middle of the chaos, Captain Hester was the tactical brains for the squadron to achieve national objectives.

In addition to the challenges, Coffey and Hester’s platform that evening expended all missiles, engaged suicide drones with their guns at “extremely low altitudes,” and landed with a live, still dangerous missile that had failed to launch.

Coffey and Hester demonstrated what the military values: decisive effects. Achieving efficient violence under extreme conditions is the essence of operational success. Captain Hester’s actions were groundbreaking not because of her gender but because they exemplified leadership in combat.

Some women, like some men, are not suited for combat roles. If we need to strengthen requirements for service members to serve in some units, we should do so. There are men who won’t meet those requirements either. But blanket rules stating that women are not suited for combat roles do a disservice to America. If the military’s mission is to achieve decisive effects, then disqualifying half the population from contributing at the highest levels undermines that mission.

We can’t claim to care about the military’s ability to achieve decisive effects while excluding women from combat roles. The contradiction subverts our claim that we value results over diversity. If we are to value results, we need to value results. We don’t need to make special rules to select women for decisive positions. When given the opportunity, they rise to the challenge. But if we make rules that exclude them, we weaken our ability to achieve decisive effects.

Unenforceable Ideals

Unenforceable ideals are contradictions in which two things cannot be true at the same time.

We can’t be ‘for’ taking action to remove undocumented immigrants while at the same time ‘against’ requirements for employers to hire legal residents. Turning off the demand for undocumented labor is the first step to resolving illegal immigration.

We need to support employers’ requirements to hire legal residents. Or we could approach the solution from another direction. We could help businesses, expand work programs for immigrants, and accept more legal immigrants.

We can’t oppose overturning Chevron deference while also opposing a new administration’s ability to change the rules. If we support limiting presidential power as outlined in the Constitution, Chevron deference is incompatible. When the executive branch can use Chevron deference to make laws, those laws will change with every new administration.

We need to support the premise that the people’s representatives make the law, not federal agencies.

We can’t claim to care about the military’s ability to achieve decisive effects while excluding women from combat roles. The contradiction subverts our claim that we value results over diversity. If we are to value results, we need to value results.

We need to value the ability for the military to achieve results. That means maintaining rules that enable women in combat roles.

May God bless the United States of America.

Share this post