Can beer and the NFL unite America?

What a ridiculous question.

Team Colors and Community Ties

Recently, I was in my local grocery store early on a Saturday morning, wearing a Kansas City Chiefs hoody, though I now live in the Mountain West region. It’s August, but many mornings are cool year-round when you live at 6200 feet elevation.

For those of you unfamiliar with the Chiefs, they are a professional American football team. I was born in Kansas City and grew up watching Chiefs games. As a kid, my favorite players were Christian Okoye and Derrick Thomas. There were enough fans in my town that church let out early when the Chiefs played the first game on Sunday so everyone could be home by kickoff.

While shopping this particular Saturday morning, a woman I didn’t know passed and remarked she hated my sweatshirt. The comment might elicit a negative response in many scenarios.

I gave the obvious response, “Thank you!” The Chiefs have won three of the last five Super Bowls, played in another, and have the world’s biggest pop star on our side (that would be none other than the illustrious and acclaimed singer-songwriter Taylor Swift). Chiefs’ colors attract some attention. I followed the stranger’s challenge by predicting Bo Nix and Sean Payton would make our division tough this year. I’m less than two hours north of Denver, and most people who comment on my team colors are Denver Broncos fans.

She laughed and said she was a Dallas Cowboys fan. After sharing her thoughts on her team, she went about her shopping way.

In my experience, that’s a pretty normal encounter with fellow NFL fans. I’ve come to understand that if I’m going to wear team colors, I will meet other fans who expect I’m current on events, and I will share brief conversations with strangers about the league. If you’re going to wear Chiefs colors, you need to know the Las Vegas Raiders took us out behind the woodshed and bloodied our mouths on Christmas Day last year, Russell Wilson is now with the Pittsburg Steelers and not the Broncos, Bo Nix won the starting Broncos quarterback job, and the Los Angeles Chargers brought in Jim Harbaugh to right the ship.

Many of these conversations start with a pseudo-challenge or feined insult. But they end up with smiles and fist bumps, even when we root for rival teams.

May we strive for the same in all of our encounters. We have differences, but we should emulate the respect NFL fans share for each other, even when we root for rivals. Part of that respect is how we interpret intent—we need to orient our perspective to assume others mean us no ill will. And part of that respect is that we mean no ill will towards others.

Humans are inherently social animals; we support and are supported by our communities. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle extensively explored this notion.

Philosophy of Society

Aristotle (384 to 322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and scientist. He is one of Western philosophy's most important founding figures, and philosophers still study his works today. At a time when the world had few texts for education, Aristotle created texts that we still use 2000 years later. His ability to systematically explore and document various fields formed the cornerstone of Western education and encouraged critical thinking across diverse disciplines.

Aristotle studied under Plato and later tutored Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects across philosophy, politics, and science.

Aristotle’s concept of the "social animal" is foundational to his philosophy. He posited humans inherently form communities to survive. He detailed this concept in his work Politics, which explored society's origin, structure, and purpose.

He declared,

Man is by nature a social animal; an individual who is unsocial naturally and not accidentally is either beneath our notice or more than human. Society is something that precedes the individual. Anyone who either cannot lead the common life or is so self-sufficient as not to need to, and therefore does not partake of society, is either a beast or a god.

Society is natural, and humans are inherently driven to form social bonds. Society exists primarily to enable citizens to live a good and virtuous life. Happiness can only be developed within a community. Every person has a role to fulfill, contributing to the common good and supporting individual development and well-being.

Individuality and Community

Let's use Aristotle's logic that flourishing comes from living well within a community to conduct a thought experiment that examines individuality and community:

Humans have a duty to support our communities if society precedes the individual, and we can’t survive outside of it. This interdependence defines human social structures.

If we must support society at the individual level, humans from varied backgrounds must be able to support their community. Individual liberty is the means to express our contribution to society.

Liberty is necessary for human development. Liberty enables us to make choices, leading to personal growth. We all require individual liberty because individuality promotes vibrant and supportive communities.

To secure liberty for ourselves, each of us has the duty to ensure liberty for others. We are all a part of humanity. Some would strip rights from others. One day the bell will toll for us. When one of us loses our rights, we all lose.

Acknowledging that others will make choices, we must accept that some will be different from our own. Embracing differences fosters a tolerant and resilient society.

To willingly accept others making different choices, we must build mutual respect for those choices. We cultivate this respect through shared experiences and consensus-building.

One way we share and build consensus is to engage in communal activities, such as drinking beer together. These shared moments allow us to bridge differences, understand new perspectives, and reinforce our communal bonds.

Presidential Perspectives

We don’t need the fermented grain and hops liquid we know as beer, but we need the community we gain by sharing beer. We build consensus by forming communities.

A quote from President Abraham Lincoln:

I am a firm believer in the people. If given the truth, they can be depended upon to meet any national crisis. The great point is to bring them the real facts, and beer.

Beer represents community, and we need community.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, on the occasion of signing the repeal of prohibition, said:

I think this would be a good time for a beer.

FDR highlights a great point. When is a good time for a beer?

Classrooms and Communion

We can’t confine the philosophy of individuality and community to classrooms or sports rivalries. It extends into our personal lives.

In September 2017, I led a squadron that stood watch over America day and night, ready to provide decisive effects at all times worldwide. It was our privilege to provide combat capability for the nation.

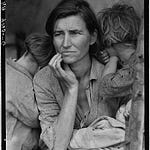

That same month, one of our teammates passed away. Most of the squadron traveled to the member’s small hometown for the funeral, with support from our sister squadrons for the watch.

We arrived the day before the funeral to attend the visitation. Due to the small town, I expected a small gathering. I was mistaken. When we arrived, dressed in Service Dress Uniform, we were greeted by more than a thousand people who had traveled from neighboring communities for the service. The Catholic Church was full, with a line stretching out the door and around the block. The crowd made way and welcomed the squadron past the line.

The family had reserved the squadron the front two rows of the beautiful church. Ushers led those who wished to share in the Sacrament of Communion to the priest. I wanted to participate in Communion, but being Protestant, I crossed my arms over my chest to demonstrate I could not participate in the ceremony as a Catholic.

The priest looked at me with unmistakable grace, made the sign of the cross on my forehead, and prayed for me and the squadron. I have seldom felt such love and unity in our shared grief as I did during his prayer for us.

We helped lead the ceremony the next morning. The squadron carried the body to the grave, stood at attention, saluted the flag during Taps and the gun salute, and cried in place.

At the request of the deceased member’s father, the squadron remained behind at the gravesite following the service. We pinned our combat “wings” on the casket and shared a beer.

The father said he had wanted to travel to his son’s duty location to have a beer with his son and his military friends, but he never got the chance. He brought out several coolers at the gravesite to share that beer with us alongside his son.

I know we didn’t all have the same views. The squadron was a melting pot. We had long-established Americans, immigrants, men and women, LGBTQ members, and kids who grew up from Brooklyn to rural Nebraska. We had only one commonality—we all raised our hands to volunteer to serve, and it was our privilege to provide combat capability for the nation.

That September morning, we set aside our differences to share a second communion over a beer. No priest stayed to say a prayer. Instead, we told stories about the fallen with his parents at a gravesite in America’s heartland.

Can beer and the NFL unite America?

Beer and the NFL alone can’t help fix societal issues. But they represent a seed of shared experiences that bridge divides and strengthen community bonds.

Instead of asking if beer and the NFL can unite America, let’s rephrase the question.

Should we orient our perspective to assume strangers don’t mean us ill will, even when our views are opposed?

Should we intend no ill will towards others, even when we disagree with their choices?

Should we set aside our differences, respect the individuality that strengthens our communities, and share communion?

May God bless the United States of America.

Postscript.

Today marks the 52nd consecutive week, or year, of I Believe's audio version. In addition to researching the topics, I’ve learned a ton about audio editing and production.

I recorded the first audio version with the built-in computer microphone in one take. Because I didn't use or even have audio editing software, I couldn’t edit any portions of the audio that weren’t good.

But I knew it was important to start. I knew I would be unsatisfied with the quality, and I would make it better. Much of my professional life has focused on innovation through relentless process improvement, which may be the most critical lesson ingrained in Air Force Weapons School students. I may no longer study or teach there, but you don’t forget those lessons.

After a couple of episodes, I started using a decent dynamic microphone. I learned to use professional audio software, Adobe Audition, to enhance audio sections and reduce background noise and unwanted sounds. I created, changed, and recreated a podcast intro. The introduction is 12 seconds long because I personally hate watching a video and wasting precious minutes listening to a prolonged introduction.

I discovered ElevenLabs technology, which opened up a world of audiobook voices as storytellers. I audio-dubbed my voice and recorded two podcasts in which my voice spoke foreign languages, including Spanish and Ukrainian, along with the English version. My audiobook characters give extra variety to each episode and help highlight alternating points of view.

If you only read the articles, thank you. I invite you to try out the audio version. The varied voices bring extra clarity to the sometimes complex topics. You can subscribe at Substack, where you will get a written and audio version on the same screen, or to Apple Podcasts and Spotify podcasts. Or enter your email below.

Can Beer and the NFL Unite America?