In principle, we should be against Social Welfare programs.

And maybe ‘against’ isn’t the right word. It's not that we're ‘against’ social programs. We can’t love our country and not love our countrymen. So, we’re not against Americans who need social programs. We're not against the social programs themselves, even though we acknowledge their inefficiencies, because they still manage to help our fellow Americans.

But if half of American families rely on social programs, that means the rules designed to enable individual Americans to succeed have failed.

We are ‘against’ social programs because the goal is for Americans to succeed as individuals and not need social programs.

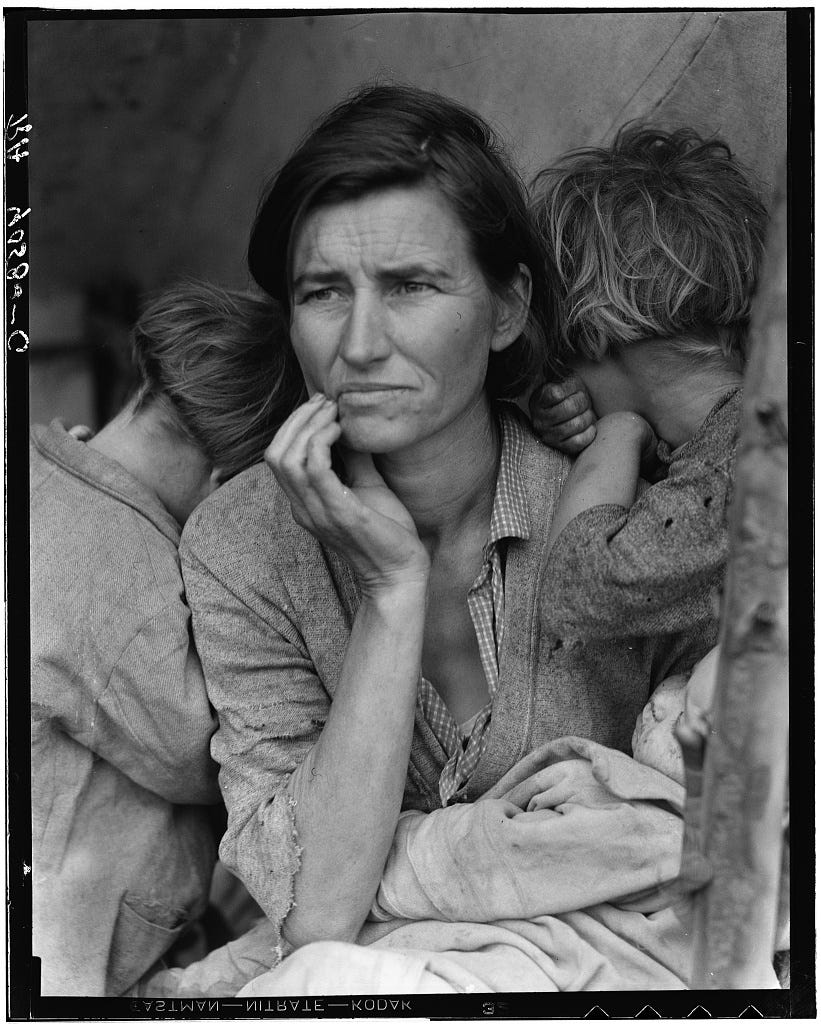

Florence Owens Thompson was born Florence Leona Christie in 1903 in Indian Territory, now Oklahoma. A mother of seven children, Florence struggled to support her family during the Great Depression after her husband died of tuberculosis in 1931. To survive, she traveled with her children and other relatives as migrant farm workers from Oklahoma to California, picking cotton and other crops.

In March 1936, Florence and her family were traveling on US Highway 101 in California towards Watsonville. She intended to work in the lettuce fields of the Pajaro Valley. However, their car broke down near a pea pickers camp in Nipomo.

A photographer, Dorothea Lange, found her there. Lange was working for the Resettlement Administration (later the Farm Security Administration) and was concluding a month-long photography trip when she came across Florence and her family in the camp. Lange took several photographs of Florence and her children.

Florence became an iconic figure of the Great Depression through the photograph that became known as “Migrant Mother.” Lange described the encounter:

I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions. I made five exposures, working closer and closer from the same direction. I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it. (From Lange's "The Assignment I'll Never Forget: Migrant Mother," Popular Photography, Feb. 1960).

Personal accounts of the day since 1936 reveal some irregularities in the reporting. Nonetheless, the image became one of the most enduring symbols of the Great Depression, highlighting the intense struggle and enduring spirit of countless Americans during that time. The photographs were published in newspapers and magazines nationwide. They became a symbol of the plight of migrant workers and the desperate conditions faced by many Americans. This exposure helped draw attention to the need for aid and led to increased government action to support the destitute workers and social programs nationwide.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) enacted numerous social programs as part of his New Deal, a series of reforms enacted during the Great Depression to address widespread economic hardship, unemployment, and social strife. These programs included union protection programs, the Social Security Act, programs to aid tenant farmers and migrant workers, banking reform laws, emergency and work relief programs, and agricultural programs. The programs helped lift the nation out of the depths of the Great Depression.

At the same time, the New Deal had downsides. Some downsides were obvious, as they excluded or marginalized black Americans, women, and other minority groups. Further, the programs were expensive and led to significant increases in government debt.

Other downsides are less obvious. The New Deal created a dependency culture wherein individuals and communities rely more on government assistance than on self-reliance or local and state initiatives. This dependency stifles innovation and the motivation for self-improvement.

The New Deal also shifted American expectations of government permanently. Before FDR, Americans had a laissez-faire view of government. After, intervention in the economy and individual lives was more acceptable.

Today, government intervention in individual lives is a near expectation.

The US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Human Services Policy released data analyzing social program participation in January 2023. That study found:

Half of American families with children receive benefits from social programs.

Nearly 30% of individual Americans receive benefits from the programs.

Those are pretty high numbers. There are 330 million people in the US. If 30% of them receive social program benefits, that means 99 million Americans receive social program benefits. And let’s repeat the first one again. Half of American families with children receive benefits from social programs.

The study suggests that a substantial portion of the population depends on government assistance. We can view this dependency in different ways. First, as a necessary support system that helps stabilize and provide for families in need. Second, as a potential issue where too large a portion of the population relies on government aid. This is unsustainable and indicative of broader economic problems.

Both can be true at the same time. It's not that we're ‘against’ social programs. We can’t love our country and not love our countrymen. So, we’re not against Americans who need social programs. We're not against the social programs themselves, even though we acknowledge their inefficiencies, because they still manage to help our fellow Americans.

But if half of American families rely on social programs, that means the rules designed to enable individual Americans to succeed have failed.

In principle, we should oppose social programs, but not because we don’t love the people who need them to survive.

We should be against social programs because if half of American families need them, that means we have a systemic failure of the system.

Let’s consider an example, highlighted by a statement I hear often, “That job isn’t worth paying someone well to do it. They need to pull themselves up, move on, and find a better-paying job. And they need to get off the government dole.”

To make our example easier to follow, let’s call this job “dishwasher.”

If we judge, and the rules support, that the dishwasher job isn't worth paying someone a decent wage to do it, they might go to night school, move on, and find a higher-quality job. But in the meantime, they get social program dollars. When we make rules that don’t enable all individuals to succeed from their work, we open the door for social programs.

When a job consistently pays wages that aren’t enough for workers to sustain themselves without additional government aid (like food stamps, housing assistance, or healthcare subsidies), the employer relies on taxpayer dollars to supplement their employees’ incomes. These rules allow businesses to maintain profitability by offloading some of the true costs of labor onto the American people.

Let’s stay on our logic train. The first dishwasher does move on and finds a higher-paying job. Then the second dishwasher finds a better-paying job. And the third, on and on.

But, the business owner fills the dishwasher job as a low-paying job and continues to fill it as a low-paying job year after year, making it a permanently funded taxpayer-subsidized job.

If half the jobs in the country don’t pay well enough for American families to thrive without social programs support, we end up with…half of American families that need social programs.

Every year, the dishwasher receives money from their fellow Americans in the form of social program dollars that help them put food on the table. The person washing the dishes changes, but the American people keep paying for the dishwasher anyway.

Some might say the taxpayer is subsidizing low-skill Americans and not the business. However, the point remains—it isn’t appropriate for taxpayers to subsidize workers, businesses, or the government at all.

This is a systemic problem. We perpetuate many jobs as low-wage, not because they inherently must be low-wage but because the system encourages low wages.

Further, the cook only makes $2 more per hour than the dishwasher, because if the American people will subsidize the dishwasher, why not the cook too? When there’s no upward pressure for higher wages for dishwasher jobs, there’s no wage pressure for other jobs.

This creates a cycle in which individual workers may advance to seek better opportunities, but the systemic problem remains the same.

The first part of the systemic problem is Americans aren’t succeeding on their own with the business rules we have in place now. We cut business taxes, but without a drive to raise wages along with the tax cuts, those dollars don’t trickle down to workers. Trickle-down economics doesn’t work.

The second part of the systemic problem is that funneling money through the government is inherently wasteful. The majority of that money is absorbed by administrative functions. Government programs perpetuate themselves. Government agencies don’t intend to eliminate themselves—they want to be functional. Lifting Americans out of poverty with social programs doesn’t work, or at least doesn’t work very well.

The American people paying government officials to send their money to an individual living in poverty doesn’t make sense. They just wasted 70% of it funneling it through the bureaucracy. Instead of the government acting as a bloated middleman, Americans need to earn sufficient money from their work, and the rules need to support wages high enough for individuals to succeed.

We need leaders to make the rules work for individuals. We don’t need rules that work just for businesses, and we don’t need rules that work for the government to support more Americans to get social program dollars. One helps businesses; one helps the government. Neither helps the American family.

I recognize and value the role of social welfare programs in supporting vulnerable populations.

But our broader goal should be to reform the system to promote independence and reduce dependency. We need to address the root causes of why half of American families with children need social programs.

America is an individualist nation. We need to prioritize policies that enable personal responsibility and self-sufficiency rather than giving businesses tax cuts or expanding inefficient, burdensome government assistance programs.

Individualism can only thrive if we set conditions that enable individuals to succeed.

May God bless the United States of America.

Postscript.

Raising the minimum wage is a crude way to improve resources for American families. It’s not a great mechanism because it’s too politically divisive, but establishing a minimum full-time wage representing a rate no less than the poverty level plus 50%, assuming the worker and three dependents for that locality might work.

I invite you to read Horses and Sparrows to consider that idea.

A way to improve resources for American families and support small businesses at the same time would be to give businesses tax cuts once they prove that none of their workers needs social program support.

I invite you to read or listen to Earned Income Tax Credit and Small Business Taxes for that idea.

Amending the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 to require directors and officers of publicly traded corporations to act in the best interests of the corporation, its shareholders, and its workers would give workers a seat at the wages table.

I invite you to read The Future of Work: A Stakeholder Approach to consider that idea.

Systemic problems require systemic solutions. It’s been nearly a hundred years since the advent of FDR’s social programs lifted the country out of the depression. We won’t fix the system overnight, and it will take more than one approach working together.

Share this post