We are endowed with radical freedom, but this freedom is inherently linked to societal obligations and responsibilities.

Where is the line between personal liberty and our obligation to society?

What about when others disagree with our healthcare decisions?

We are Condemned to be Free.

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980) was a French existentialist philosopher, playwright, and novelist. He saw first-hand two world wars and the German occupation of France during World War II. Sartre’s philosophy explored the nature of existence, freedom, consciousness, and the human condition. He described himself as an anarchist; the only cause he believed in was human freedom.

The central concept of Sartre’s philosophy was the existentialist view that individuals create their own meaning in an indifferent universe. He believed in radical freedom and the inherent responsibility that freedom enabled. He disavowed belief in a deity. As an atheist he posited individuals are free to make their own choices and create meaning in a world that does not provide meaning.

But he also posited that we are condemned to be free. This freedom is not liberating. It’s a prison of condemnation because it comes with weighty personal responsibility for our choices and their consequences.

For Sartre, the absence of a predetermined purpose meant that each person must define their essence through actions. This freedom is inescapable. The responsibility it entails can feel burdensome, as individuals cannot blame their circumstances, society, or a deity for their choices and outcomes. They are fully responsible for defining their own existence.

Sartre could have been a libertarian if not for his belief in social responsibility and the collective struggle for justice and equality. He strongly rejected authoritarian structures and traditional societal norms. He did not advocate for anarchism as a governance structure; he was more of a socialist.

In sum, Sartre was, in part, a radical individualist. But his blend of existentialist thought, atheism, and commitment to social responsibility make him a complex philosophical figure.

Individualism and social responsibility seemingly contradict. Let’s keep digging into this unique nature of individual freedom.

There’s another concept that intersects with existentialist thought…to explore it, let's head to the American West.

Ride for the Brand!

Ride for the Brand is a phrase from the American West originating from cattle ranching culture. It embodies loyalty, dedication, and commitment to a group or cause. It refers to a cowboy's loyalty to the ranch owner or the "brand" of cattle he worked for.

The saying is widely known in the West. It symbolizes standing by your commitments, working for the greater good of the community or organization you're part of, and upholding the values and principles that define it.

Possibly the earliest written reference to Ride for the Brand is Western writer Zane Grey’s 1934 novel Code of the West. The Code of the West isn’t a set of laws; it’s a social contract. Those who broke the code became social outcasts. This social contract, underpinned by unwavering loyalty to one's commitments, was crucial in shaping social norms and expectations.

Ride for the Brand isn’t an ethos of blind loyalty. It’s a duty to uphold your commitment to a community or group's collective values and goals.

The American West’s “Ride for the Brand” demonstrates how individual freedom and social commitment coexist. We make choices, and those choices come with obligations. By riding for the brand, we commit to honoring our obligations.

We all make choices, either willingly or by the station of our birth.

Our choices represent individual freedom. Some choices are forced on us. Our parents and grandparents choose our place of birth. Our elected representatives choose other societal conditions on our behalf. We choose to pay taxes, to obey laws, and to respect the rights of others. Though we don’t explicitly make every one of our choices, they are our choices nonetheless.

These choices come with obligations.

Edmund Burke, the world’s decisive Conservative philosopher, said we have “obligations to mankind at large, which are not in consequence of any special voluntary pact.” Burke recognized that even if we didn’t explicitly choose the station of our birth, we still have obligations resulting from those choices.

We commit to honoring our obligations. We make commitments to ourselves, our communities, and our society. These commitments represent our social contract.

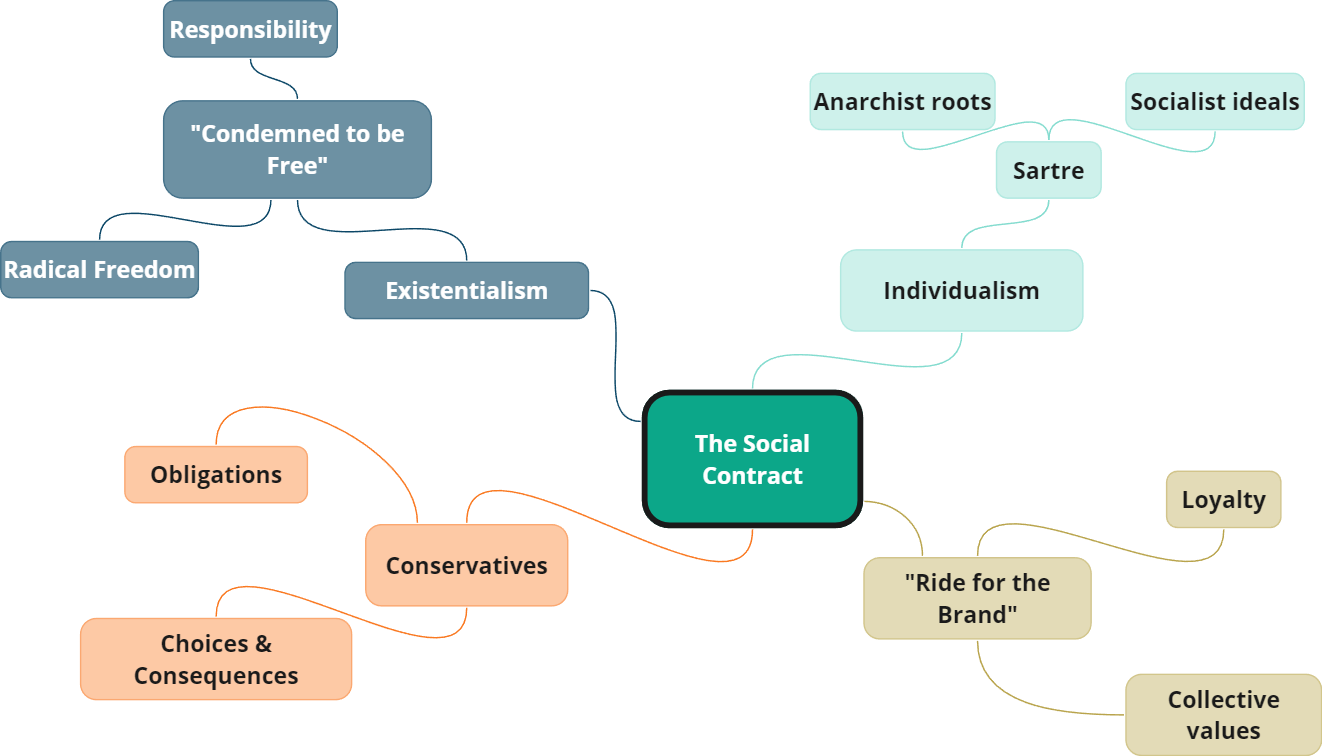

Here’s a mind map that graphically represents our text.

Our commitment to radical freedom is a component of the social contract. So are our societal obligations and the consequences of our choices. Our loyalty and collective values, expressed by our unspoken law to ride for the brand, are a part of our social contract.

While we each have the personal freedom to define our existence, we do so within a social framework that levies responsibilities and consequences. Our individual choices echo through our social structures, impacting others. They influence and are influenced by our collective values and commitments, much like our duty to ride for the brand.

Let’s have a concrete example…

Measles Vaccinations

Measles is a highly contagious viral disease. It’s so contagious that up to 90% of people near an infected area can become infected if they aren’t vaccinated. Measles stays in a room for up to two hours after the infected person leaves. You can catch measles just by entering this room in those two hours.

Dr. Peter Hotez, co-director of the Center for Vaccine Development at Texas Children’s Hospital, says, “For every 10,000 children infected with measles, 2,000 will be hospitalized; 1,000 will develop ear infections with the potential for permanent hearing loss; 500 will develop pneumonia; and 10 to 30 will die.” Possible long-term effects of measles include memory loss, seizures, and blindness; these effects can emerge as long as eight years after infection.

Babies are a genuine concern. You can’t vaccinate a child until they are 12 months old. Michael Mina, MD, PhD, assistant professor of epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, identified that before the vaccine, measles was “likely associated with at least half of all childhood deaths from infectious diseases.”

But there’s good news! There’s a really good vaccine to protect against measles infection. Two MMR shots are 97% effective at preventing measles infection.

Unfortunately, as of a week ago, 17 states here in America have measles outbreaks.

In sum, we’ve established measles as a highly contagious viral disease that is preventable by the individual choice to be vaccinated. When enough people are vaccinated in a community, the entire community will be disease-free. Let’s consider a philosophical case study of public schools, existentialism, and loyalty to our communities.

Do you have a radical freedom right to refuse the vaccine? Yes. You can do so on whatever grounds you prefer, the most common being a religious exemption. You absolutely have a right to make your own healthcare decisions. The government should have no say in the matter.

At the same time, if you choose to use public resources such as schools, this choice violates our social contract. You can’t refuse to adhere to public safety standards and, at the same time, use public resources. This personal choice echoes through our social structures, impacting others.

If you choose to participate in social structures such as sending your kids to public schools, you have to ride for the brand. When you make the choice, you take on the responsibility. Doing so upholds the collective values and goals of your community.

Alternatively, you have a right to refuse to participate in society. There are Supreme Court cases that establish your precedent to home school for religious reasons. Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972) supports parental rights. In the case, the high court ruled that a parent’s First Amendment right to free exercise of religion was more compelling than the state’s interest in educating their children. Courts have repeatedly found home education a viable pathway to citizenship.

There’s another consideration here: the role of government officials. Do officials first have a responsibility to protect the rights of individuals? Or do they first have a duty to uphold the public interest, including public safety? Yes, and yes.

Government officials are responsible for protecting America's bedrock—individual liberty. There is no higher obligation.

But when individual choices infringe on the rights of others, officials have a duty to protect the individual rights of the people. When individuals make choices that endanger others, they violate our social contract. Just as officials are responsible for maintaining individual rights, they have a responsibility to conserve the institution. In this case, we are still protecting the rights of individuals to make their choice. But if they choose to threaten public safety, they shouldn’t also be able to choose to use public resources.

There is no higher principle than individual liberty. No matter your belief in a deity, individuals are inherently free to make their own choices and create meaning in the world.

At the same time, this freedom comes with weighty personal responsibility for our choices and their consequences.

We are condemned to be free.

When we choose to participate in society, we must honor our social contract and commit to upholding our community’s collective values and goals.

We ride for the brand.

May God bless the United States of America.

Share this post